The Lithium Crossroads

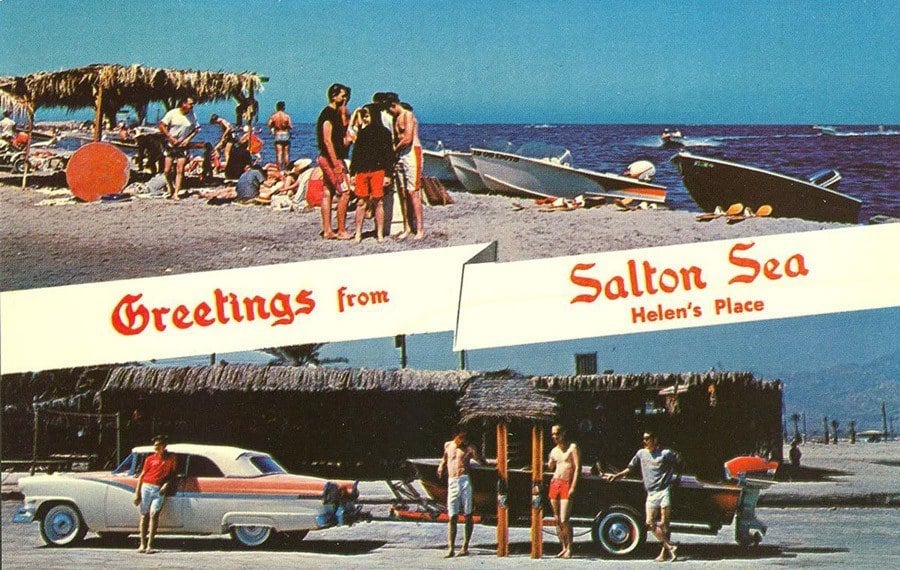

Once a beachfront haven for celebrities, Southern California’s Salton Sea turned toxic long ago from too much agricultural runoff and too little fresh water. Today, few fish survive, while hazardous dust drives the highest asthma rate in the state.

Yet lithium is luring businesses back to the Salton Sea because vast deposits of this silvery mineral lie deep beneath the lakebed.

Three energy companies are racing to refine technology to extract lithium from the Salton Sea’s geothermal brine, with large-scale operations anticipated within a year. About 375 million lithium-ion batteries could be created from these stores, more than the total number of EVs currently on United States roads.

All of which means that Imperial County and the Salton Sea stand at a crossroads: How will mining impact longstanding environmental hazards? Can lithium extraction create sustainable jobs?

Critical Questions

For insights on lithium in the Imperial Valley, we welcomed Teto Huezo of Jobs to Move America, Daniela Flores of the Imperial Valley Equity and Justice Coalition, and Lul Tesfai of the Irvine Foundation during Smart Growth California’s recent webinar, “Learning from Lithium Valley.” It was the second in our Rural Funders Working Group series “Who Benefits from Community Benefits?” examining how rural areas navigate green energy projects. (Our first webinar focused on offshore wind in the Humboldt Bay and our May 13th conversation examines Kern County energy storage).

Over the past year, Irvine invested $7.5 million in the region to bolster coalition building and workforce development so that green infrastructure investments, driven by the Biden-era Inflation Reduction Act, deliver meaningful community benefits. Irvine is among a number of funders supporting work in Imperial Valley, including the Latino Community Foundation, the 11th Hour Project, and the Sierra Health Foundation’s Community and Economic Mobilization Initiative.

“There’s a lot riding on this,” Tesfai said of the lithium developments. “There needs to be intentionality, pause and real community voice in deciding what development looks like in the region.”

Imperial Valley Challenges

Tucked in California’s southeastern corner, Imperial County is a land of stark contrasts. Its fields grow a significant amount of the nation’s produce, yet one in five residents faces food insecurity. Corporate farms dominate, growing water-intensive crops like lettuce and alfalfa, yet many who live there (80% of whom identify as Latino) struggle to access clean water.

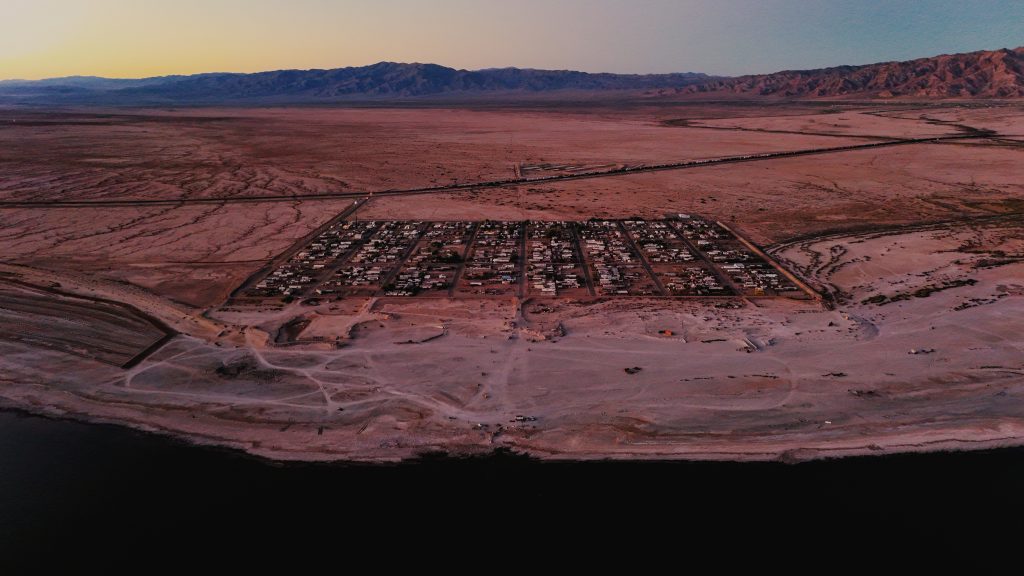

Then there’s the Salton Sea—a sprawling, troubled giant. Nearly the size of San Diego or all of New York City’s boroughs combined, this vast inland lake has spent a century soaking up fertilizer runoff. Now, as it shrinks, it unleashes the nation’s largest toxic dust source, choking the air and threatening public health.

Like many rural areas, Imperial County’s local government operates with limited resources. To help, philanthropies have partnered with the Institute for Local Government, offering technical assistance so municipalities can secure grants and access essential tools larger cities take for granted.

Bombay Beach by Pablo Villagomez

Amid the region’s uncertainty, government officials sometimes hesitate to demand benefits from energy companies out of concern for job and revenue losses.

In 2023, the Legislature passed a lithium excise tax on energy companies, backed by Imperial County supervisors. Yet supervisors have resisted calling for enforceable job agreements or community benefits.

Shifting the Narrative to ‘Stay’

Daniela Flores is one of many residents who want clearer guarantees on the benefits of lithium extraction.

A Calexico native who grew up working at her parents’ swap meets, Flores earned a master’s in public health from UC Berkeley. Returning home during the pandemic, she found Imperial County leading the state in COVID-19 deaths.

When county officials were reluctant to enforce state mandates on school and business closures, Flores mobilized thousands of signatures, pressuring Governor Newsom to visit and witness the crisis firsthand. His visit delivered much-needed resources—and inspired Flores and others to launch the Imperial Valley Equity and Justice Coalition, or IV Equity.

“People like me, we want to stay here,” said Flores, who’s engaging a new generation of local activists by creating Southern Winds, a locally written and illustrated magazine telling the story of Imperial Valley. “We’re working to shift the narrative from ‘leave’ to ‘stay.’”

A Coalition for Change

Supported by Irvine and other partners, IV Equity and its allies recently launched Valle Unido Por Beneficios Comunitarios (United Valley for Community Benefits).

The coalition brings together local groups like Comité Cívico del Valle, Earthworks and IV equity, along with national organizations such as Jobs to Move America, the American Civil Liberties Union—monitoring ongoing air quality concerns—and the United Auto Workers (UAW), which is working to establish job pipelines for future battery manufacturing. Their collective mission is to secure community benefits through government-issued permit requirements, public funding conditions, or other mechanisms.

“There is a very clear difference between agreements that represent good intentions and those that are enforceable,” said Huezo, of Jobs to Move America, which helped negotiate a multi-state agreement with North America’s largest bus manufacturer and has since expanded to industries such as wind energy, school buses, and, most recently, lithium mining.

Last year, local groups brought a lawsuit against one of the companies gearing up to extract lithium, saying the environmental impacts had not been adequately studied. In December, that suit was dismissed, further clearing the way for extraction to begin.

Meantime, Imperial County has established a voluntary “Good Neighbor Community Benefit Agreement Program” aimed at fostering collaboration among industry, government, and community members. But companies are not legally obligated to adhere to the commitments.

“Our goal,” Huezo said of the coalition, “is an agreement where companies commit to shared decision-making with community organizations.”

Salton Sea by Katherine McKinley

Pioneering ‘Green’ Lithium

The Salton Sea sits atop one of the most active geothermal fields in the United States. Hot water and steam pumped up from deep below the earth have powered geothermal power plants to generate electricity since the 1980s.

The lithium extraction process underway essentially piggybacks on this geothermal energy operation: As the brine is sucked up, lithium is harvested before the fluid is returned to the earth. Known as direct lithium extraction (DLE), it’s a pioneering process that’s more environmentally friendly than traditional open-pit mining and evaporation fields used in China and South America, where extraction destroys habitats and large swaths of land.

But advocates are concerned about the fresh water required for direct lithium extraction, since water is at a premium in the arid Imperial Valley and a lack of fresh water is making the Salton Sea increasingly toxic. They also point out that direct lithium extraction has never been tried at a commercial scale.

Beyond Extraction

Tesfai, Flores, Huezo and say the real game changer isn’t just pulling lithium from the ground—it’s harnessing lithium to spark a regional manufacturing industry that powers the future, from batteries to electronics to cutting-edge energy storage.

Most electric vehicle batteries are produced overseas, and even those made in the U.S. depend on lithium sourced from other countries. Establishing a domestic battery manufacturing hub with a local lithium supply in Imperial County could mark a new era for American-made green energy. (For an engaging read on this vision, including the history of Lithium Valley, make sure to read Charging Forward: Lithium Valley, Electric Vehicles, and Just Future, the latest book by Chris Benner and Manuel Pastor.)

When lithium extraction is up and running, it’s estimated to bring about 600 jobs. By contrast, a lithium-based industry could generate over 20,000 jobs, according to research from New Energy Nexus. This approach would also reduce the need to transport lithium, cutting greenhouse gas emissions. The Torres-Martinez Desert Cahuilla Indians could play a pivotal role in leveraging their sovereign status to help create opportunities for their community.

Next Step: Avoiding Sacrifice Zones

In closing the conversation, we asked Flores and Huezo how funders interested in this topic can stay engaged, and what messages they wanted to leave.

Flores’ answer was from the perspective of a lifelong resident of an “overlooked community.”

“When there’s a larger benefit for the greater good,” she said – like creating renewable energy – “sometimes small communities get sacrificed. We already feel like we’ve been sacrificed for the agricultural industry. We want to be protected this time.”

Jobs to Move America is hosting an event March 13th, 2025 in Culver City to showcase its work in the Imperial Valley; they’re also hosting a funder tour of the Salton Sea in November. Reach out to get more information.

Finally, the Strategic Growth Council’s BOOST technical assistance program, in collaboration with the Institute for Local Government, is looking for support to continue a second year of its programming. Email Karalee Browne (kbrowne@ca-ilg.org) for more information.

Stay tuned for our next discussion on community benefits May 13, 2025 from 2 – 3:30 PM at the Rural Funders Working Group. We’ll hear how community groups in Kern County are secure community benefits for solar storage facilities with the help of on intermediary, Sustain our Future.

♦♦♦

Diana Williams is Program Manager for TFN’s Smart Growth California and coordinates the Rural Funders’ Working Group and the San Joaquin Valley Funders’ Collaborative.

Email Diana (diana@fundersnetwork.org) with questions, if you’d to join our meetings, or for recordings and notes from our discussions on Lithium Valley, the Humboldt Bay, or prior meetings.